By Melanie Ralph

Amid many pressing issues of 2021, you would be forgiven for missing some big news published in a full page spread of The Australian newspaper back in August. Noel Pearson, academic and community leader, boldly declared that the “teaching debate” has ended “once and for always.” The ‘debate’ Pearson refers to is apparently “between teacher-directed explicit instruction and inquiry learning – variously called discovery learning, problem-based learning and critical thinking.”

The idea that teachers could use both explicit instruction and inquiry-based practices simultaneously, and in addition to other approaches, seems lost on Pearson. Evidently, it’s lost on many others, too, including former Education Minister Alan Tudge, various journalists, and right-wing think-tankers at the Centre for Independent Studies (CIS). Worse still, it seems several teachers themselves have also hopped on the bandwagon of pitting one teaching strategy against another.

Pearson’s article cites a report titled Why Inquiry-based Approaches Harm Students Learning’ by John Sweller, which attempts to debunk inquiry learning – a learning approach that emphasizes critical and creative thinking and which prioritizes the student’s role in the learning process. As a result of the report, the CIS asserts that “the cognitive science on learning is settled,” and Pearson writes that “we need no more evidence about what works.”

But as a teacher with over 14 years of experience, I would argue that “what works” in a classroom will change according to context. There is no one strategy that works in every situation. Any good teacher will tell you: what works in Period 1 may not work by Period 4, and that quality teaching involves constant change, reflection, and modifications – ideally in a supportive and collaborative environment. When I am a supervising teacher to practicum students, I warn them: do not believe anyone who tells you there is nothing left to learn about good teaching.

Though Pearson believes it is “embarrassing” for our country that Sweller has not been in the driver’s seat of curriculum design, I argue it is more embarrassing to be oblivious to the fact that there is no “once and for always” approach in education; that it can and never will be ‘settled,’ and the question of how best to teach is precisely what draws teachers back to it every day. Further, it is only the very best teachers who embrace this and demonstrate what educational philosopher Maxine Greene describes as a willingness to “present themselves to the young as also incomplete; in quest somehow, with new questions always arising.”

But the lack of teaching experience of Pearson and others has not stopped them from identifying what they perceive to be the ‘problem’ in Australian schools. The real enemy, according to Pearson, is the “progressive educationalists pursuing the dream of John Dewey and Lev Vygotsky.” Or according to Jennifer Buckingham of the CIS, the problem is those teachers who believe in “romantic” notions that education is about more than “filling children up with facts.” Buckingham’s criticism is baffling, given Romanticism’s valuing of the individual, “the life of the imagination” as well as the “belief in human potential” (Halpin), ideals most people would hope teachers uphold.

It’s often proposed that what children need most is a new fleet of the “best and brightest” people to join the teaching profession to replace the idealistic dreamers currently stuffing up the NAPLAN scores. But it’s difficult to see why any of our brightest would set foot in a classroom when we see the continued endorsement by Tudge of “basic” approaches to teaching that essentially embody a return to ‘chalk and talk’ methods.

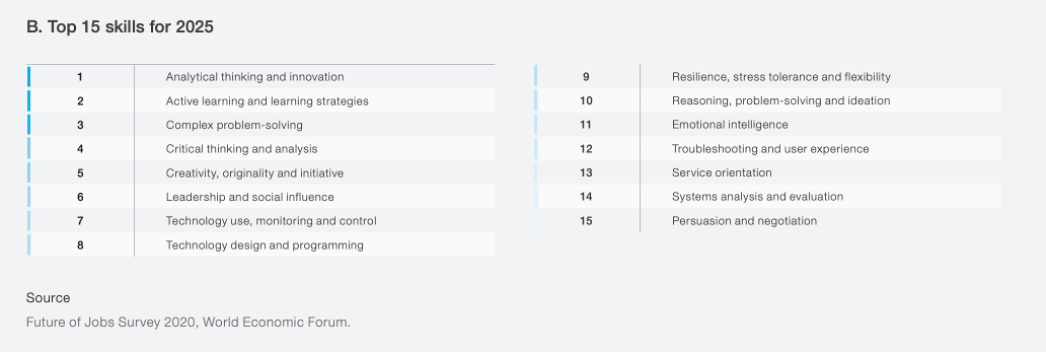

Not only does this contribute to the “long and inglorious history in the Australian media” of teacher bashing, but the idea of using ‘basic’ approaches – i.e more chalk and talk – is completely at odds with the kind of innovation needed in our schools to prepare students for an unpredictable and complex future. In fact, the World Economic Forum’s report, Schools of the Future, warns that “there is an urgent need to update education systems to equip children with the skills to navigate the future of work and the future of societies,” and that “primary and secondary school systems have a critical role to play in preparing the global citizens and workforces of the future.”

Furthermore, the report calls out the education systems in developed and developing economies that “still rely heavily on passive forms of learning focused on direct instruction and memorization, rather than interactive methods that promote the critical and individual thinking needed in today’s innovation-driven economy.”

Yet, flying in the face of this report, back-seat teachers like Tudge and Pearson, as well as right wing-think-tankers, continue to gripe about teachers being too creative, too innovative, even too fun. More broadly, this ‘debate’ often boils down to what author Alfie Kohn describes as a caricature of progressive education, the umbrella under which inquiry learning or critical thinking sits. Kohn argues that the caricature portrays progressive education as a “do whatever makes you happy” style of teaching where teachers believe “maybe you’ll learn, maybe you won’t, that’s OK.”

This misleading portrayal is not uncommon. Last year, in a YouTube video, Dr Julie Townsend, headmistress of St Catherine’s School in Sydney, described inquiry learning as “inferior” and proudly boasted that it is “not practiced” at her school. Further, she describes inquiry learning as an “ideology.” Townsend’s belief that inquiry learning is a failed ideology is mirrored by Natalie Wexler, who in a recent article blamed progressive education and Dewey “acolytes” for students struggling to learn.

Time and time again we see anecdotal stories of bad teaching being used to demonize progressive teaching. For instance, Wexler makes her case against it by describing the experiences of teacher Eric Kalenze, who claims during his education master’s degree in America in the 1990’s, “no one ever told” him that he would need to provide background context for students during a novel study. Instead, he says he was told to focus primarily on “inquiry and hands-on activities.”

It seems when Eric heard ‘inquiry’ and ‘hands-on’ he misinterpreted these terms to mean ‘surface level’ and ‘arts and craft.’ Before writing off entire university teaching programs and claiming that they teach “ideology and fads”, as Tudge has done here, it would be wise to consider Eric’s firsthand reflections. In the article, he recalls when he first became an English teacher that during a study of The Great Gatsby, his lessons included “spending two or three days” looking up word definitions, “finding magazine ads” using symbolic colours in the novel, and “making collages.” Only “after a few years” did he realise that “his apparently engaged students weren’t grasping Gatsby’s significance” and that his approach did not place “enough value on building students’ knowledge through explicit instruction.”

So, Eric stopped the collages and started teaching the history and context of the novel.

Quality teachers would find Eric’s epiphany to be laughable if it wasn’t for the sad fact that many students evidently missed out on an enriching and engaging novel study. Let me be explicit: the fact that it took him years to realise his students were engaged only in surface level busy work is more revealing of Eric’s limitations as a teacher, and perhaps the lack of mentoring and coaching in his school, than it is of the supposed inefficacy of inquiry and progressive education.

So, why the outrage? It’s the PISA scores, stupid.

The calls for more direct instruction and the death of inquiry are often underpinned by hot air about our “decline” in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) scores. One problem with PISA results (and there are many) is that they are cited by politicians and journalists to make alarmist claims about our “creeping failure” and the fact we are “not keeping up.”

Not keeping up with who? Well, Singapore and other top performing nations, according to Tudge. He often laments that we are being “overtaken by our Asian neighbours” and that “in Shanghai the average 15-year-old mathematics student is performing at a level two to three years, on average, above his or her counterpart in Australia.” He claims that when he points this information out to people in his speeches, they are “typically shocked.”

But who is genuinely shocked that China ranks higher than us in PISA scores?

Writer Saga Ringmar points out that “Chinese children have been taking tests since the arrival of their milk teeth” and that therefore their “system breeds PISA champions, but it also ruins young lives.” This leads me to question why on earth would we envy a system that “is widely criticized by its own educators, scholars, and parents for generating toxic levels of stress and producing graduates with high scores, low ability, and poor health”? (Zhao, Selman and Haste). While some may view this as a system worth emulating, it’s difficult to imagine that parents in Australia would value PISA scores over their child’s wellbeing.

Teach less, Learn More

In 2021, when Tudge wasn’t in a in a flap about Bruce Pascoe’s “Dark Emu” or blocking pesky teachers on Twitter, he was busy using PISA scores to justify his 10-year plan to “lift” education standards; to “roar back and put ourselves once again in the top band of education nations.” Teaming up with him at a CIS event in June, Noel Pearson teased out some of the inspiration behind this plan, claiming that “the best systems are those systems that are favouring teacher led instruction…and that’s what high performing systems in Southeast Asia are doing.”

But Pearson is misleading here. In fact, though “Singapore’s education system may produce students who lead in reading, mathematics, and science…they receive failing grades when it comes to innovation.” According to Medium, the “Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s was evidence that Singapore’s strict pedagogical model was not preparing their youth for the reality of the 21st century globalization and knowledge economies.”

Tudge, Pearson, and his CIS counterparts would no doubt balk at the name of the education initiative launched in 2005 by the Singaporean Ministry of Education (MOE): it was titled Teach Less, Learn More.

Former Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said it was an attempt to encourage teachers to “streamline the syllabus, reduce rote learning and adopt teaching methods that would better engage students and prepare them for the real world” (Singapore Infopedia).

Further, Dr. Pak Tee Ng, of the National Institute of Education (NIE) at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, points out the title of this initiative is “actually a very good reminder to us as educators, that more of the same teaching is not the way to inspire better learning…we tried to move our focus away from being able to do well in examinations, to appreciation of subject, to critical thinking, to creativity.” Additionally, Professor Tan Oon Seng, of the NIE, states that the pedagogical approach in Singapore has been a move towards teaching that is more “student-centred” where teachers see themselves as “facilitators…even as innovators.”

This is all starting to sound a bit Romantic, isn’t it?

Though Tudge eloquently acknowledged that our decline in PISA scores could be the result of a “bunch of other things”, it strikes me as odd that these ‘other things’ are increasingly sidelined in the sport of teacher blaming. For instance, Tudge says the last 20 years of education in Australia has been “shameful” (I disagree), and Pearson suggests teachers deliberately seek to “impede” children’s learning and that they “leave kids to figure it out for themselves” in the classroom, further characterising teachers as incapable and uncaring.

So, what has led to the decline in scores? Well, according to Pearson it can be summed up in the mumbo-jumbo mantra associated with the Direct Instruction program he promotes: “If the student has not learned, the teacher has not taught.” Are we willing to apply this same logic to the health sector? For example: if the patient doesn’t live, the nurse has not nursed? This is nonsense. It is not to say that teachers should not aim to improve – the good ones always do. But it is crude to suggest that teachers are solely responsible for the “bunch of other things” (often beyond their control) that can cause a student to ‘not learn.’ For example, social issues such as poverty, mental health, and family violence can negatively impact children’s educational outcomes.

This idea, coupled with “simplistic measures purported to improve the quality of teachers and the quality of teaching through testing, judging, “fixing” or removing “underperforming” teachers” (Stephen Dinham) is part of what’s led to teaching being described as a “profession in distress.” The distress has less to do with whether teachers are directly and explicitly instructing kids (which they are), and more to do with that “bunch of other things” Tudge glossed over – namely “low pay, a lack of respect and increasing workloads” (The Guardian).

With all this in mind, it’s hard to fathom how Pearson and Tudge would expect the same academic results of Singapore here in Australia whilst promoting less innovation in the classroom, and that their proposed “fix” involves a continued “anti-intellectual bias” which discredits and devalues teachers. Even more unfathomable is the funding and endorsement of the American Direct Instruction program.

Explicit/direct instruction vs Direct Instruction

Let’s clarify what is meant by direct instruction (lower case), and Direct Instruction (capitalised).

According to Allan Luke of QUT, direct instruction, sometimes called explicit instruction, “refers to teacher-centred instruction that is focused on clear behavioural and cognitive goals and outcomes.” Luke disputes Pearson’s claim that as a result of inquiry learning, children are being “left to teach themselves” in Australian classrooms, reporting that in fact “several major meta-analyses and reviews have identified explicit instruction as a major instructional approach in contemporary schooling.”

Clearly then, direct instruction is already the norm in our schools. I would even argue that perhaps direct instruction should be the focus of our scrutiny if Tudge is so worried about PISA scores. Given that reports show “almost half of Australian school students [are] bored or struggling,” might it be, that student disengagement has something to do with lowering test scores? Hm, I wonder…

Using direct instruction is not newsworthy. Good teachers are already using it, but they are using it in conjunction with a range of other strategies. There is no ‘debate’ about lower case direct instruction; we know it is integral. But, to exclusively use direct instruction is to simplify teaching, which is, in reality, a very complex practice. In fact, Alan Reid, Professor Emeritus of Education at the University of South Australia, asserts that “the idea teachers are straitjacketed to one approach is an affront to their professionalism.”

Even a Dewey-acolyte-Romantic like me uses direct instruction alongside other teaching strategies. Let’s use a thesis statement lesson as an example. To teach thesis statements, I would likely be at the front of the classroom to introduce the topic explicitly. I might be using visual aids, thinking aloud, and annotating examples. I’d be checking for understanding frequently, formatively assessing, and moving between elements of Fisher and Frey’s Gradual Release of Responsibility framework; for instance, I might ask students what they already know about thesis statements, then model a thesis statement for them, then we might do one together and students can collaborate and independently try for themselves. I would also allow room for some productive failure to occur. This means that “success is not assured, but rather that there is the possibility that students will make errors that must be resolved” (Fisher and Frey).

Buckle up, because in the middle of all this – on a good day – there might even be some laughter, or dare I say, fun? (Read: student engagement).

Some of these strategies I learned in university, others I learned on the job, and much of my practice comes from reflection – both personal and with colleagues – and ongoing professional reading. Frankly, it would be ridiculous to look back at my university degree and blame them for any gaps in my teaching practice; good teaching involves a focus on quality and continuous improvement long after that final uni essay is submitted.

But the teacher-led utopia of yesteryear that Pearson dreams of involves a lot more teacher-led instruction than the picture I just painted. Pearson is dedicated to the dominant teacher-talk method known as Direct Instruction (or ‘DI’ – capitalised), which was developed by Americans Siegfried Englemann and Carl Bereiter in the late 1960s.

Luke describes DI as an instructional approach which involves teachers using a “a step-by-step, lesson-by-lesson approach to teaching that has already been written for them. What the teachers say and do is prescribed and scripted and accompanied by a pre-specified system of rewards.” It is “tightly paced” and “linear” and involves “the strict scripting of teacher behaviour” in an attempt to “place quality controls on the delivery of the curriculum” (Luke). It’s unsurprising that Pearson would favour this strict, linear approach, given he describes himself as an “old-fashioned “chalk and talk” teacher” whose schools have reputations for being places where “even the grass sits up straight.”

Yet, in his publication Visible Learning John Hattie says there is “no place” for “test-driven surface instruction,” likening these methods to those used by Mr Gradgrind, the tyrant teacher in Dickens’ Hard Times. Mr Gradgrind is described as having “a cannon loaded to the muzzle with facts” ready to blow students “clean out of the regions of childhood at one discharge” (77). Alarmingly, Mr Gradgrind’s grim, mechanical approach accurately mirrors the Direct Instruction model espoused by Pearson.

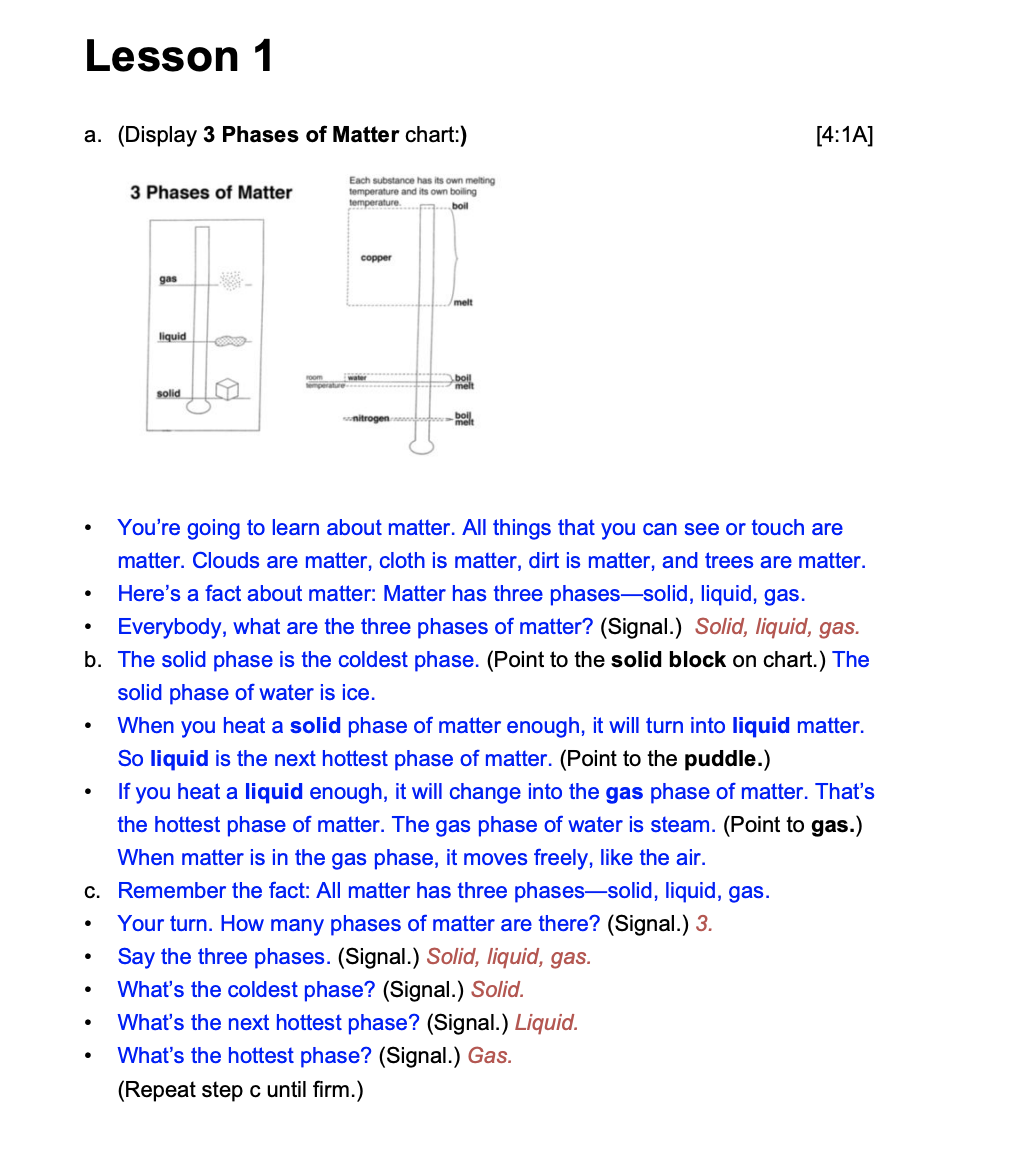

A quick YouTube search of DI in practice shows teachers holding scripts while they briskly read out prompts to children who are encouraged to answer orally and in unison when given an “auditory signal,” such as when teachers snap, tap, or clap as a verbal cue, or when they say “get ready” or “what word” (Journal of Direct Instruction), as seen in the clip below.

The Journal of Direct Instruction (2004) spins the idea that teachers are still able to be creative and artful when using DI, and that “like actors, DI teachers are performers who put life into scripts.” Yes, apparently teachers can still bring “warmth, excitement, and life” to these scripts, and can relax as the pressure to be “spontaneous” is alleviated. But are we really willing to lower the bar this far for kids and teachers? Is it too Romantic to expect educators to be highly effective communicators (without a script), able to employ superior levels of emotional intelligence, and have the ability to spontaneously interact with young people? Are these not core aspects of the profession?

In the example below (taken from a program which costs $129) it’s difficult to see how one might ‘breath life’ into the teacher’s lines which are in blue. Student responses are in red.

Having fun? I’m not convinced that even Meryl Streep could bring this script to life in front of an audience of Year 9’s in period 4.

Pearson cites Hattie’s emphasis on the obvious need for teachers to be explicit and clear as proof that what Australian kids need is more teacher-led instruction. But he’s misconstrued the point here, perhaps focussing too much on Hattie’s point that “some didactic imparting of information and ideas is necessary,” but missing the part where he writes, “in too many classrooms there needs to be less teacher-dominated talk, and more student talking and involvement” (73).

In the ratio of blue to red in the script above, it’s difficult to see how Hattie’s statement aligns with DI.

Additionally, if students ‘don’t learn’, rather than using blanket statements such as the ‘teacher has not taught’, Hattie provides a more nuanced perspective, saying “it is more likely” that content needs to be “re-taught using a different method” and that “it will not be enough merely to repeat the same method again and again” (84). In the script example above, the instruction to “repeat step C until firm” is mind-numbing: I feel bad for the children who might quietly mumble a parroted answer so as to not draw attention to the fact they actually don’t understand what matter is, despite how many times the teacher might have repeated step C.

Einstein reminds us: “Any fool can know. The point is to understand.” Therefore, quality teachers would ask, do the kids here deeply understand what matter is, or have they simply figured out the right words to say when the teacher taps? And if they don’t understand, shouldn’t teachers ask themselves, “what can I do differently?” rather than repeat an ineffective speech?

For instance, after (explicitly) teaching students about the historical context of Shakespeare’s Macbeth, I was heartened when a student put his hand up to ask, “Miss, was the Renaissance a good or a bad thing?” I pondered the question. “I think it was good,” I answered, “partly because it’s the reason I get to stand here engaging with you intellectually, because if we were in medieval times, you would likely be out farming, and I would be taking care of domestic duties in a home…we wouldn’t even be having this conversation without the Renaissance. In fact, given life expectancy in medieval times, I’d be nearing the end of my life right now.” At this point, a female student raised her hand to object, saying emphatically, “Nah Miss, you’d be dead by now if it was medieval times. You would’ve been burnt for being a witch ‘cos you don’t have kids and you’re not religious.”

“Yes, Ella. Great point!” Despite the gruesome imagery, I was delighted – this student didn’t just know the historical context, she understood it.

But these moments of unpredictable learning would be lost if I were to script my lessons in the style of DI. Apparently, according to the Journal of Direct Instruction (2004), scripts are preferable because they “relieve teachers of the responsibility of designing, field-testing, and refining instruction in every subject they teach” (88). An Australian teacher on Twitter echoed this same idea of being relieved of the burden of creativity, likening the possibility of not having to plan lessons as being a “utopia”, in which “teachers are freed up from creating a bespoke curriculum every day” to have “greater time for focus on instruction, formative assessment, coaching, observation, and professional learning.”

But isn’t “creating a bespoke curriculum every day” kind of, you know, our job? Certainly, our best and brightest teachers already do consider curriculum design and delivery to be critically important because of its necessity for meeting the needs of diverse children. Not only do our best and brightest find curriculum design an extremely fulfilling and satisfying aspect of teaching, but they would no doubt be confused by those who bemoan it.

With such a laser focus on ‘debunking’ progressive strategies, Pearson and others have neglected the value of creativity and innovation in classrooms. For instance, it would be refreshing to hear them refer to Michael Fullan’s work on Deeper Learning, a global partnership that works to “transform the role of teachers to that of activators who design experiences that build global competencies using real-life problem solving.” Fullan explains, “Wise policy makers will leverage and further stimulate promising deep learning developments because they come to see the necessity and desirability of having citizens who are steeped in the global competencies.”

These competencies include creativity, critical thinking, collaboration, and character, and unsurprisingly reflect the skills the World Economic Forum predict will be most in demand in the future. But of course, wise policy makers would already know this, wouldn’t they?

A closer look at DI

So, where is DI actually happening? Though it’s creeping into more urban schools, for instance on the Gold Coast, it’s mostly associated with programs in remote schools that are part of Noel Pearson’s organization Good to Great Schools Australia (GGSA). Former Prime Minister Tony Abbott described Pearson as a “prophet” for his work in setting up an Academy of schools that are, according to the ABC, “unlike any other state school” because of their strict DI programs. Sounds a bit ideological to me.

In 2017, when then Education Minister, Simon Birmingham, suggested that there were ‘green shoots’ of success because of the program, he chipped in an additional $4.1 million to their already huge pool of $37 million in federal and state funding since 2010 (ABC). But it is an absurd notion to suggest that observable ‘green shoots’ as a result of DI – such as marginally improved NAPLAN scores (though this is contested) – are enough to justify the demonization of inquiry and progressive learning.

Human students deserve better

There are many reasons to disagree with DI, but one of the most pressing reasons is the way in which it may inadvertently perpetuate racist practices in education. Here in Australia, Stewart Riddle of the University of Southern Queensland, suggests it’s possible that DI programs in remote schools “are no better than historical attempts to make Aboriginal kids more “white”” and that there are some resonances to missionaries when we are “teaching Aboriginal children in remote communities a version of literacy that is more about success in NAPLAN tests than success in life.”

Similar concerns were noted when the Standing Committee on Indigenous Affairs met in 2016 to discuss key aspects of educational opportunities and outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. Here, Correna Haythorpe, Federal President of the Australian Education Union, explained that in some instances, DI programs have “actually replaced programs such as bilingual education and the curriculum programs that acknowledge Aboriginal language.”

Haythorpe recalled visiting a DI school in a remote community and observing that the “school really had almost erased the Aboriginal language of that community in their classrooms. There was no evidence, other than the children sitting in the classroom, that I was in an Aboriginal community.” In comparison, she notes the school “not too far down the road,” which did not use Direct Instruction, was “vibrant” in its “acknowledgement of the local language and that direct connection with culture.”

Given the lack of nuance in the delivery of DI and the fact that these programs are American, it’s unsurprising that there are reports of “kids getting bored of the program quickly” (AEU). In fact, John Guenther of the Batchelor Institute reports that “schools with a DI intervention had a faster rate of decline in attendance” than schools that did not use DI. This speaks volumes about the way in which Aboriginal children may feel about Western education systems, such as DI, that effectively erase Indigenous cultural identity and fail to promote a sense of belonging for the students.

Haythorpe saw this for herself, telling the standing committee she saw a student in the NT who “actually said to the teacher, ‘Are we doing direct instruction today, Miss?’ When she said yes, he took off because he did not want to participate in the program.” She also noted the impact the program can have on attendance, saying students were “not wanting to come to school while DI is being taught and coming to school at lunchtime when they know that the program is finished.”

But alas, it would be Romantic to value a student’s identity, engagement, and happiness when there are NAPLAN scores to improve, right?

Nonetheless, Pearson reminds us in a CIS speech that “Aboriginal children are no different from other human children. They have the same capacity, and they have the same learning mechanism of other human students.” Yet, if they are indeed “no different” from others, why do they require a program that is so vastly different to the education that the majority of other “human students” in Australian schools receive? It seems that policymakers have become distracted by their desire for improved test scores for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students and have not considered the potential harm of DI programs beyond the classroom.

For instance, in an article by American author Alfie Kohn, he refers to a report that followed “mostly African-American poor children from Michigan” from the age of 3 into adulthood who were “randomly assigned to DI, free-play, or High/Scope constructivist preschools.” The study found that though “the academic performance of the DI children was initially higher,” it “soon became (and remained) indistinguishable from that of the others.” However, disturbingly this study revealed that by age 15, “the DI group had engaged in twice as many “delinquent acts,” were less than half as likely to read books, and generally showed more social and psychological signs of trouble than did those who had attended either a free-play or a constructivist preschool.”

Even more troubling, some actually believe a benefit of DI in remote schools is that it provides a “relative lack of variability in teaching quality” which is “particularly attractive in schools that have many inexperienced teachers and high levels of teacher transiency.” Translation: it’s hard to get experienced staff to these schools, so let’s just lower the bar entirely and read American scripts to our “human students.”

Pearson boasts that because “we don’t distinguish between human learners,” the “biggest surprise” has been that “your stock standard Education Queensland teacher” can do a “bloody great job” with the program. Somehow I doubt Ed Qld wants to amend their objective from “a great start for all children” to “a stock standard start for all children.”

Behind the scenes, there’s nothing stock standard about the “financial irregularities” revealed in an investigation into GGSA in 2016. Former executive principal of Cape York Academy (a GGSA school), John Bray, said he felt “morally compromised” and “uneasy” when he noticed school funding being spent on flying out American DI experts, “up to 8 times a year, for two people, with flights and accommodation…that’s a lot of money.” At the time, he recalls wondering, “Why is that coming out of our Academy account when really that should be going towards our kids?”

Chris Sarra, internationally recognised Indigenous education specialist and founder of the Stronger Smarter Institute, shares Bray’s discomfort, saying it’s a “tragedy that people get rich off” DI “while poor families have to pay the price,” and that it’s “pedagogy for the poor. Good for making slaves, domestics, and farmhands. Them days are gone. Blackfullas deserve better.” Indeed, I would argue that they deserve more than a stock standard neo-colonial education.

The better way

So, what are some effective teaching methods for Indigenous students? Well, according to Dr Cathie Burgess, studies have shown that pedagogies which improve Aboriginal student engagement and educational outcomes include taking students “out of the classroom and onto ‘country’” using collaborative approaches between “rangers, teachers and community members” as well as “individually paced learning,” seeing school as a place of “belonging and relevance,” and by employing what she calls ‘pedagogies of wonder’. That is, “adults listening to the wonder of the children about their own history, culture and context and trusting children to research this rich resource.”

Examples of these strategies in action can be found on the Deadly Science Twitter feed. Started by proud Kamilaroi man, Corey Tutt, this organization aims to support “the next generation of First Nations scientists” by providing “science resources, mentoring and training to over a hundred remote and regional schools across Australia with a particular focus on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities.” Remote schools across the country have been sharing innovative lessons in which they have used resources provided by Deadly Science.

Another great example of teaching that uses a ‘pedagogy of wonder’ and is responsive to the local community and cultural setting is Tagai State College in Thursday Island, where teacher Kathryn Wemyss says students have done “extended investigations” that explore curriculum content in a way that is relevant to their lives. Examples include connecting content about floating and sinking to their experiences of dinghies and fishing. Wemyss says, “if you build from the things that they know and are interested in, you’re showing that you value that, and it makes them feel good and that they’re more engaged in their learning.”

Beyond the prattle

In some ways, I can understand the romanticised nostalgia of the back-to-basics crowd: we’d all like life to be a little more…well, basic. Predictable. Stable. But even in 1792, great thinkers like the Romantic Mary Wollstonecraft argued that children should not simply recite facts in a “parrot-like prattle” but should be “excited to think for themselves” (Vindication chapter 12).

Easing the distress in education won’t come from mimicking Asian systems and it certainly won’t come from wasting money on American programs that stifle deep learning. A good place to start is to stop the “active antagonism” of teachers in the media, as Nan Bahr says, because “it is hard to understand what a society can possibly gain from demonising the profession that holds its future.”

Just as you’d expect a plumber to arrive at your home with more tools than just a plunger, wouldn’t we expect teachers to arrive at classrooms with more than DI, or even lower-case di, in their toolkits? It is hardly revelatory that teachers already have direct and explicit instruction in their toolkits. Considerably more newsworthy is the fact that our best and brightest teachers are already aiming for more than stock standard outcomes for kids by providing engaging and creative learning opportunities. However, I’m not holding my breath waiting for full page editorials highlighting and celebrating this.

To describe teachers as ‘Romantic’ because they affix their gaze on more ambitious goals than short-term bumps in test scores, and value each child as a unique individual, is in fact a compliment, because the alternative view – that education is simply about learning facts – is not compatible with the world we live in now and the demands of the future. Instead of more children being blown out of the regions of childhood by DI programs in which teachers are loaded to the muzzle with scripts, we must nurture innovation and excite imaginations so that both students and teachers can thrive.

© Melanie Ralph 2022

Thank you for so clearly elucidating the arguments against Direct Instruction as a successful main teaching strategy. You are absolutely spot on in your points, descriptions of effects, and observations of people who promote – and make a lot of money out of it.

So true- good teachers change, adapt, dynamically transform pedagogy constantly to facilitate student learning. The students are not robots, and neither are we. Long live creative pedagogy and teacher’s agency in choosing the technique of instruction that will work best for their young people 🙂

LikeLike

Anne-Marie – thank you for your comment! I’m lucky to work with teachers like yourself who value agency and creativity.

LikeLike

This is such a good piece. Whenever I hear someone espouse the benefits of DI I feel a sense of discomfort and this articulates exactly why a narrow instructional focus in the classroom is not going to fix all the issues in education. I suspect the lack of equity in our system and the challenge in fixing this means it’s easy to jump on these bandwagons. It looks like an easy fix to claim teachers are simply bad at their job and poor outcomes have nothing to do with inequality, poverty or other social problems. I can’t believe the credence given to the CIS by some, given their obvious bias towards a particular agenda.

LikeLike

Thanks for your comment! This was a big one as not only was my critique directed at Noel but the CIS, too. Gross. Thank you so much for reading! 🙂

LikeLike

Thank you Melanie, Its great to see a well thought and thorough critique of Pearson and his focus on DI. Some excellent references too. Its very interesting that the NAPLAN results and attendance are no-where near what he implies is happening at his schools. I was particularly disturbed by Pearson’s ABC Boyer lecture #4 last December when he blamed a boys death on the school not having a DI and SoR approach. One wonders what his motive is. I tried to contact Pearson over his reliance on Hattie’s research, particularly Hattie’s rating of “Welfare Policies” as low. Pearson seems to take this seriously, I tried to get him to read the ONE study Hattie referenced to show him it has absolutely nothing to do with Welfare strategies in a Australian Schools. I suspect a subplot of the failure of his schools is this lack of priority on Welfare strategies.

LikeLike

Thank you for reading and for your comment, George. I couldn’t bring myself to get through more than ten mins of the Boyer Lecture…and I’m unsurprised he’d link a death to a lack of DI or SoR. Even in the last week or so he’s deemed NT teachers to be “failures” and blamed the Alice Springs crime wave on schools. Yikes.

LikeLiked by 1 person